Field notes on cost structures, pitfalls of comparison, and what historical datasets still teach.

Cost per foot is not a fixed number

Cost per foot can be tracked tightly for a specific job. It rarely transfers cleanly to the next job. [1]

-

Ground conditions change.

-

Drill method changes.

-

Labor, diamonds, fuel, and supply pricing changes by region and time.

-

Contract scope changes what is “included” in the number.

A mine’s internal “underground drilling cost” often excludes items a contractor must carry. Typical omissions include overhead, depreciation, transport, and supervision. Accounting practice can move the number materially. For comparisons, trends and percentages are often more defensible than absolute figures.

Diamond drilling vs percussion drilling

Historical mine tests compared diamond drilling with non-coring percussion drilling for blast holes. One recurring result was a break-even hole length. Around one operation, the intersection of cost curves sat near 18–22 ft for certain conditions. That limit moved as tooling improved.

What changed the break-even point:

-

Removable percussion bits and improved shanks.

-

Tungsten carbide tipping.

-

Lower gauge loss, which reduced reaming and reduced wasted energy.

-

Better extension steels and couplings.

A key takeaway: “best method” is conditional. The break-even length shifts with consumables, steel life, gauge holding, and the actual stope geometry.

What a “cost per foot” is made of

A direct-cost breakdown from controlled underground drilling records listed the following line items:

-

Labor and bonus

-

Diamonds and bits

-

Supplies

-

Repairs

-

Compressed air

-

Mine services

In one historical dataset, total direct cost was reported at $0.877 per foot, with labor the largest component. Diamond and bit costs were a significant second component. Mine services and compressed air also contributed.

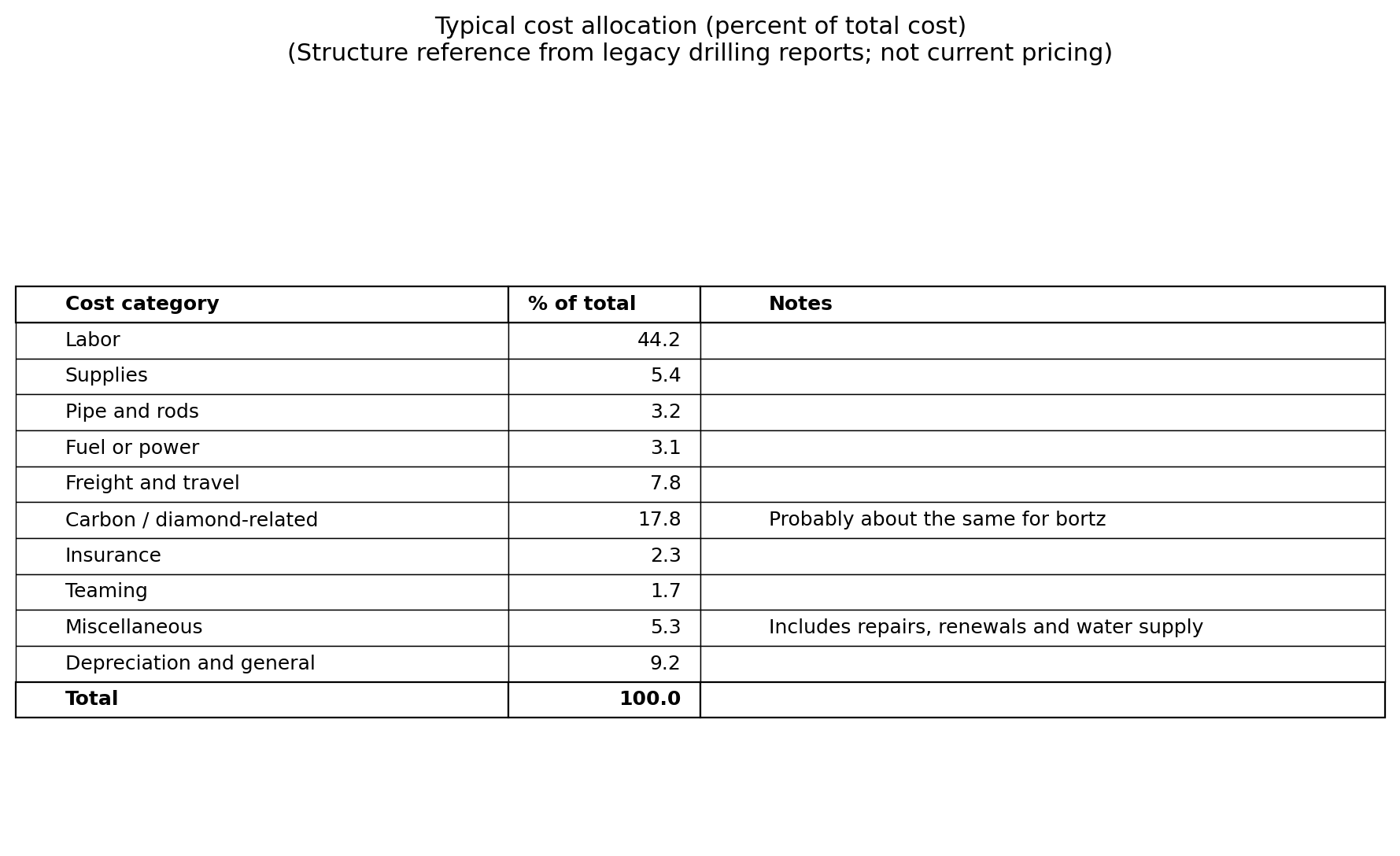

A separate large-sample summary of drilling cost allocation (surface work across multiple regions) reported the largest share as labor, followed by carbon/diamond-related costs, then freight/travel, depreciation/general, and smaller categories such as fuel/power, pipe/rods, insurance, teaming, and miscellaneous repairs and water.

Use these as structure. Do not use them as today’s price references.

Productivity metrics that matter more than “$/ft” alone

Legacy performance tables for blast-hole diamond drilling tracked:

-

Footage drilled per machine shift

-

Tonnage drilled per machine shift

-

Tonnage per foot

Those three metrics separate “fast drilling” from “useful drilling.” A higher footage number can still be poor economics if diamond consumption rises, gauge is lost, or the drilled tonnage per foot drops.

Direct cost per foot vs cost per ton

Historical tables also separated:

-

Cost per foot drilled

-

Cost per ton drilled

That distinction is important in blast-hole work. Cost per ton connects the drilling result to what the hole is for. It also reduces distortion when hole diameter or burden changes.

Bonus systems: why they are controversial in coring

Bonus systems are often unpopular in core drilling.

-

A bonus can push footage.

-

Footage incentives can also increase lost core and equipment wear.

-

The owner usually values core recovery and geological quality.

-

Recovery-based bonuses can be hard to administer fairly.

In blast-hole drilling, conditions can be more uniform and core recovery is not a factor. Footage-based bonuses can function better there.

Example: a structured underground bonus system (historical)

One mine described an underground contract arrangement with these features:

-

Company supplied equipment. Contractor maintained it.

-

Pay shifted from recovery-based to straight footage.

-

Air was charged to the contractor at a fixed rate per foot.

-

Hole measurements were spot-checked using sectional measuring rods.

-

Base price per foot was linked to the contractor’s average diamond (bortz) price over a defined bonus period.

-

Additional cents per foot were added above a footage threshold, with step increases over higher footage bands.

This is useful as a template for thinking. It links incentives to measurable outputs and to a major variable cost.

“Progressive improvement” and diamond setting practice

One reported improvement period aligned with a change in diamond size used in bits. The text described a move from large stones to smaller, sharper stones (expressed as more stones per carat). The reported effect was:

-

Lower cost per foot

-

Lower diamond consumption

-

Higher footage drilled

Mechanism is straightforward: more cutting points, lower load per stone, and more stable engagement. Results still depend on formation and bit design.

Carbon vs bortz bits: what the comparison actually tests

A European test compared hand-set carbon bits against hand-set bortz bits in limestone, breccia, and schist. Carbon bits delivered more footage per carat when the bortz stones were comparatively large. That result did not translate directly into cost per foot.

Reasons given:

-

Carbon stones had much higher unit cost.

-

Mechanically set bits reduced cost compared with hand-set bits.

-

Small, sharp stones cut faster.

-

Liability was lower if a bortz bit was lost.

-

Bortz bits required less specialized labor than carbon bits.

The note concluded that most drilling in that period was moving toward mechanically set bortz bits, with carbon specified mainly for special cases.

Practical use on a modern drilling program

Use this chapter as a checklist, not a price list.

-

Define what “cost” includes before comparing vendors or methods.

-

Split direct cost from overhead and services.

-

Track footage, diamond consumption, and recovery together.

-

Compare methods using the metric that matches the objective (per foot vs per ton).

-

Treat bonus systems as an engineering control problem. Incentives change behavior.

→ For more information about ROCKCODE’s Products, please visit: https://www.rockcodebit.com/product-support.html

→ Email us at: info@rockcodebit.com

→ Information in this article is for general reference only. For specific drilling projects and drilling bits, please consult qualified professionals. Thank you.

Source

【1】Cumming, J. D. (1956). Diamond drill handbook. (2nd ed.). Smit.

https://www.rockcodebit.com/diamond-drilling-costs-and-what-drives-them.html

www.rockcodebit.com

Wuxi ROCKCODE Diamond Tools Co., Ltd.

Average Rating